We recently shared 3 Common Pitfalls in Microservice Integration – and how to avoid them and lots of you wanted more. So this four-part blog series takes us one step back to the things you’ll be considering before migrating to a microservices architecture and applying workflow automation. You’ll have a lot of questions, right? Questions like:

- Scope and boundaries – what workflow do you want to automate and how is this mapped to multiple microservices or bounded contexts in your landscape?

- Stack and tooling – what kind of workflow engine can I use?

- Architecture – do I run a workflow engine centralized or decentralized?

- Governance – who owns the workflow model and how does it get deployed?

- Operations – how do I stay in control?

In this four-part blog series, I’ll tackle the most common questions we get asked by our users and provide guidance on the core architecture decisions you’ll have to make. I’ll give simplified answers to help you get started and orientated on this complex topic.

Because all theory is gray I want to discuss certain aspects using a concrete business example which is easy to understand and follow — a simple order fulfillment application available as the flowing-retail sample application with source code on GitHub. The cool thing about flowing-retail is that it implements different architecture alternatives and provides samples in different programming languages.

All examples use a workflow engine, either Camunda BPM or Zeebe. But you can transfer these learnings to other tools — I simply know the tools from Camunda best and have a lot of code examples readily available.

Getting Started

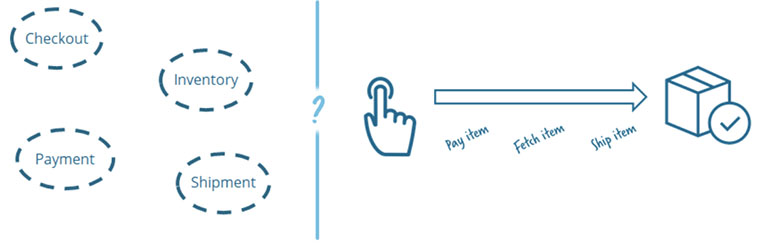

Let’s assume you want to implement some business capability, e.g. order fulfillment when pressing an Amazon-like dash button, by decoupled services:

Track or Manage? Choreography or Orchestration?

One of the first questions is typically around orchestration or choreography, where choreography is most often treated as the better option based on Martin Fowler’s Microservices article. This is typically combined with an event-driven architecture.

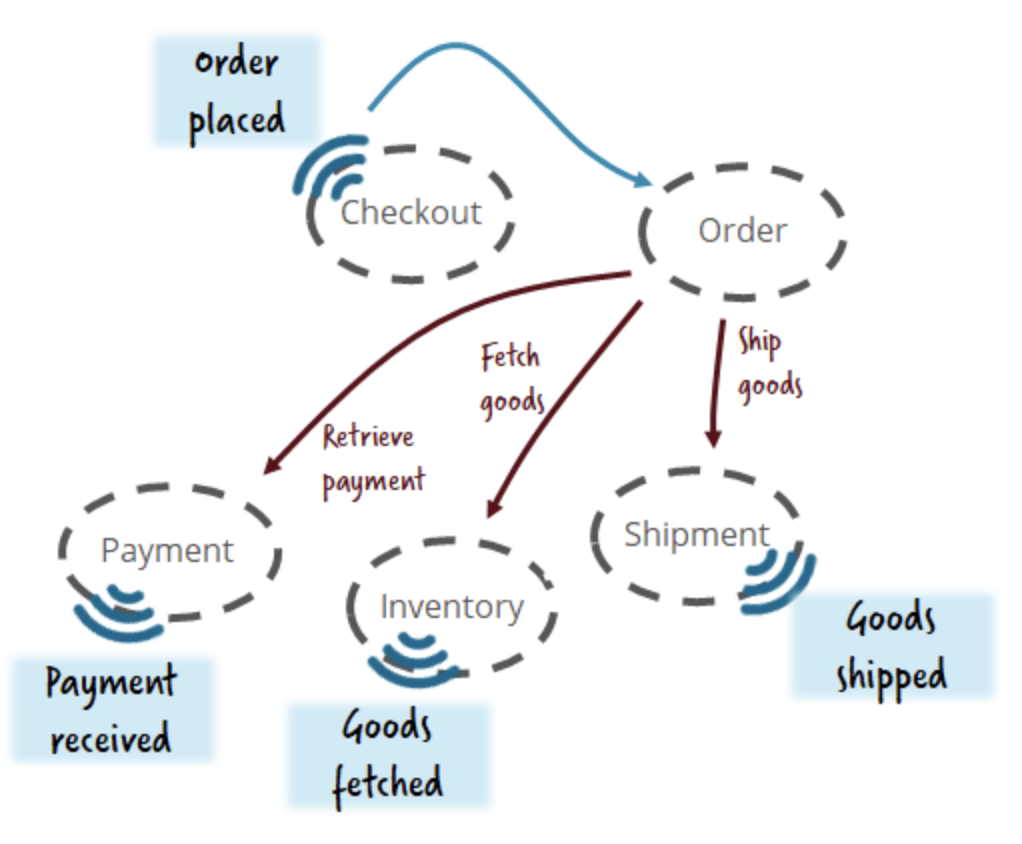

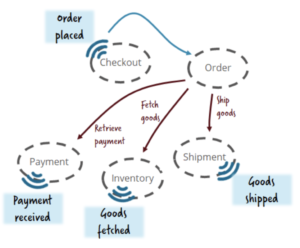

In such a choreographed architecture, you emit so-called domain events and everybody interested can act upon these events. It’s basically a broadcast. The idea is that you can simply add new microservices which listen to events without changing anything else. The workflow is nowhere explicit but evolves as a chain of events being sent around.

The danger is that you lose sight of the larger scale flow. In our example – the order fulfillment – it becomes incredibly hard to understand the flow, change it or operate it. Even answering questions like “are there any orders overdue?” or “is there anything stuck that needs intervention?” are a real challenge. I discuss this in my talk Complex event flows in distributed systems (here’s a recording at QCon New York if you’d prefer the live version!).

You can find a working example of pure choreography here.

Tracking

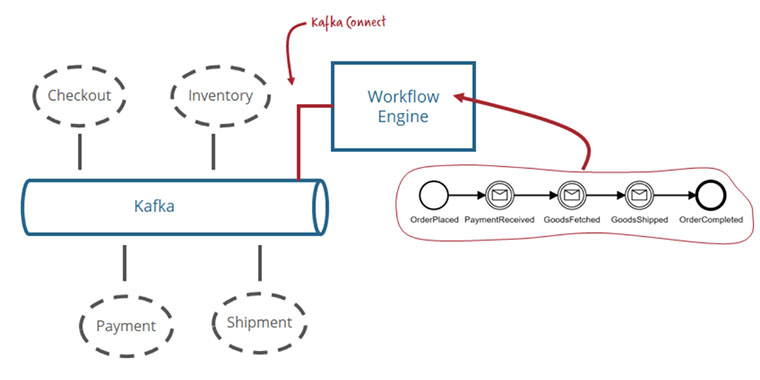

An easy fix can be to at least track the flow of events. Depending on the concrete technical architecture, you could probably just add a workflow engine reading all events and check if they can be correlated to a tracking flow. I discussed this in my talk Monitoring and Orchestration of Your Microservices Landscape with Kafka and Zeebe – here’s the slides and a recording from Kafka Summit San Francisco for those who prefer to follow along live.

Our flowing-retail shows an implementation example of this using Kafka and Kafka-Connect.

A Journey towards Managing

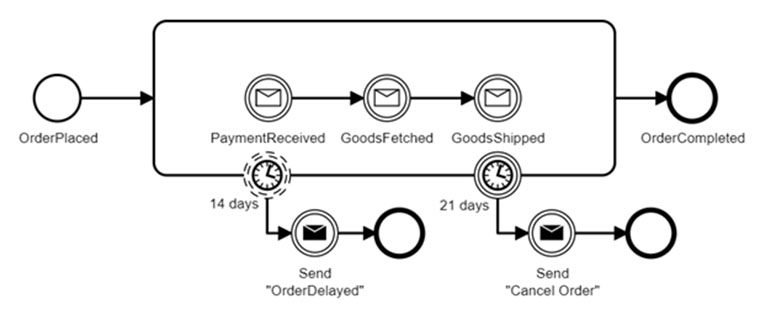

This is non-invasive as you don’t have to change anything in your architecture. But it enables you to start doing things, e.g. in case an order is delayed:

Typically, this leads to a journey from simply tracking the flow towards really managing it:

Mix choreography and orchestration

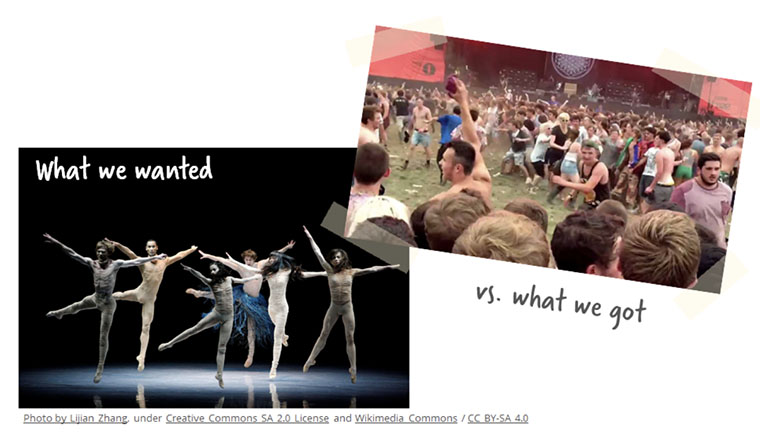

A good architecture is usually a mixture of choreography and orchestration. To be fair, it’s not easy to balance these two forces without some experience. But I’ve seen a lot of evidence that shows this is the right way to go, so it’s definitely worth investing the time. Otherwise your choreography, which on the whiteboard was a graceful dance of independent professionals, typically ends up in more like a chaotic rave:

In the flowing-retail example, that also means you should have a separate microservice for the most important business capability: the customer order!

In our next blog, we’ll discuss the role of the workflow engine and provide three alternative architecture examples that you can use to keep a lid on the chaos.

This blog was originally published on Bernd’s blog – check it out if you want to dive even deeper into microservices!