Back in March, I conducted the webinar: “Monitoring & Orchestrating Your Microservices Landscape using Workflow Automation”. You can find the recording of the webinar online, as well as the slides. Not only was I overwhelmed by the number of attendees, but we also got a huge list of interesting questions before and, especially, during the webinar. I was able to answer some of these, but ran out of time to answer them all.

So I want to answer all open questions in this series of seven blog posts – you can click on the hyperlinks below to navigate to the other entries.

In this blog, we’ll be exploring Architecture related questions.

- BPMN & modeling-related questions (6 answers)

- Architecture related questions (12)

- Stack & technology questions (6)

- Camunda product-related questions (5)

- Camunda Optimize specific questions (3)

- Questions about best practices (5)

- Questions around project layout, journey and value proposition (3)

Q: How do you deal with interfaces between systems within one business process (e.g. order fulfillment) or between multiple business processes (e.g. sales and order fulfillment)?

Architecture-wise I would not only look at the business process but at the system boundaries of your microservices. Let’s assume you have the order fulfillment microservices and the checkout microservice (the latter is what I would relate to sales — bear with me if you had other things in mind).

Within one microservice, you have some kind of freedom of choice, it mostly depends on the technologies used. I would consider all of these approaches valid:

- Two Java components calling each other via a simple Java call. You might share the same database transaction. (Only within one microservice!)

- Two components calling each other via REST.

- Two components send AMQP messages to each other.

- Two different BPMN workflows call each other via BPMN call activity. (Only within one microservice!)

If you cross the boundary of one microservice, you will have different applications that need to be decoupled. So you need to go via a well-defined API, which is most often either REST or Messaging (but could also mean Kafka, gRPC, SOAP or similar). That means you cannot do direct Java calls or use call activities (the italic bullet points above) — both would couple the microservices together too closely in terms of technology.

Q: Can you tell a few pros and cons using microservices vs call-activities?

This is related to the last answer. A call activity makes the assumption that the called subprocess is also expressed in BPMN and deployed on the same workflow engine. If this is the case, it is a very easy way to invoke that subprocess. You will see the link in monitoring (e.g. Camunda Cockpit) and get further support, for example around canceling parent or child workflows. So if you don’t have any issues with the restriction to run in the same workflow engine, call activities are great. This is typically the case within one microservice.

But if you cross the boundary of one microservice, you don’t want to make that assumption. You don’t even want to know if the other microservice uses a workflow engine or not. You simply want to call its public API. So in this case the call activity cannot be used, you use a service task or a send/receive task pair instead.

Q: How do you chain workflows spread across different microservices

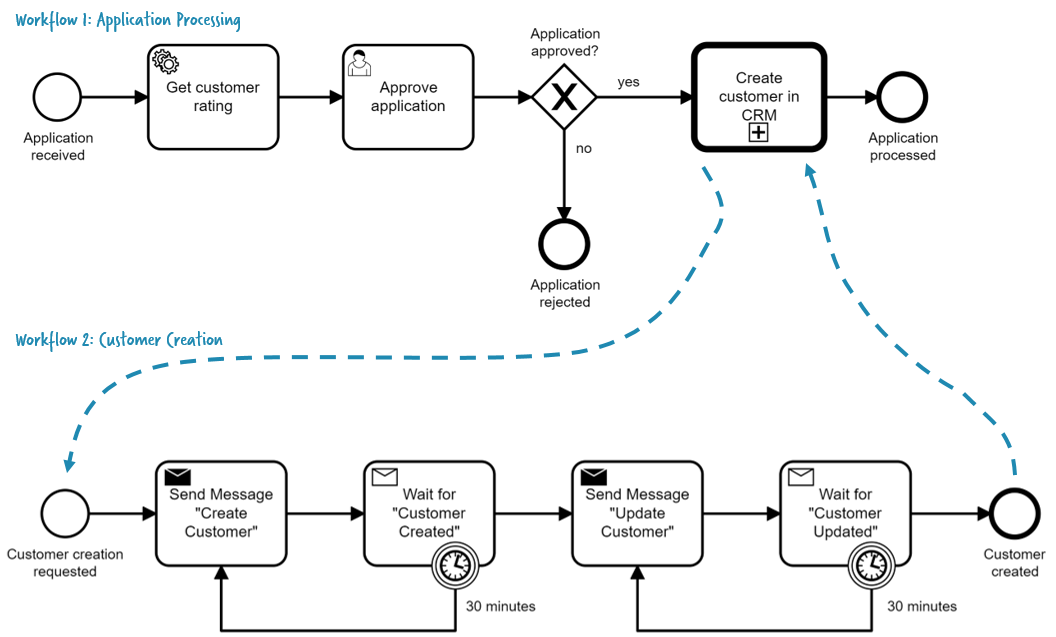

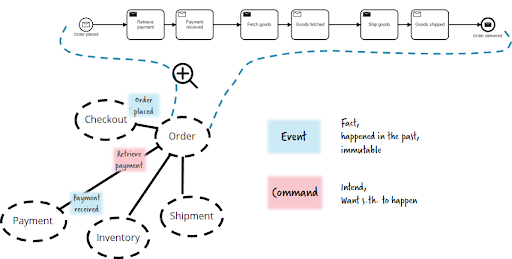

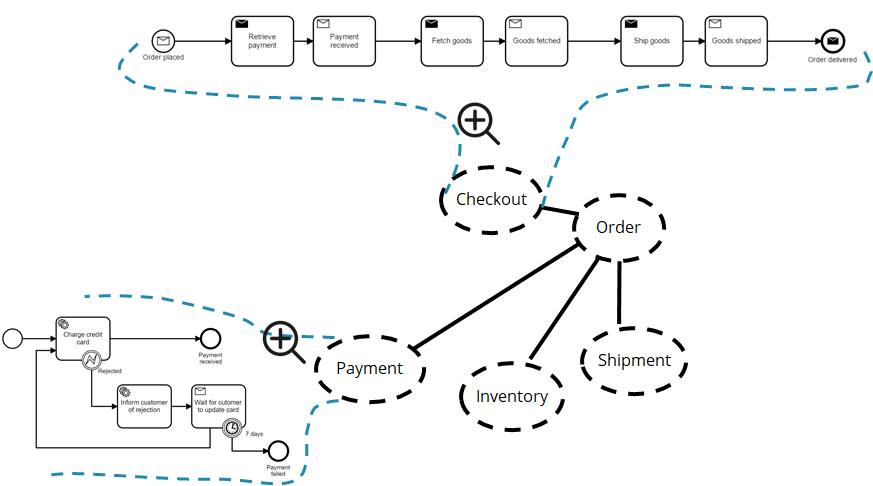

This should be partly answered by the last two answers. End-to-end workflows very often cross the boundaries of one service. Let‘s use the end-to-end order fulfillment business process as an example. It is triggered by the checkout service, needs to retrieve payment, fetch goods from the warehouse and so on.

The whole business process happens because of ping-pong of different services. The interesting part is to look at how this ping-pong is happening. And to end up with a manageable system you have to find the right balance between orchestration (one service commands another service to do something) and choreography (services reacting on events):

That means that only parts of the whole business process will be modeled as an executable workflow in a workflow engine. Some parts may end up in a different workflow engine. And other parts end up hardcoded somewhere. In the above example, payment might also have its own workflow:

This is an implementation detail. It is not visible from the outside. You just call the payment API.

You can learn more about that in my talk Complex Event Flows in Distributed Systems.

Q: Could you please send me more information about the differences between events and commands? Is that a different type of contract?

You already learned a bit about that in the last answer:

- Events are facts, it is the information that something has happened. It is always past tense. If you issue an event you should not care about who is picking it up. You simply tell the world: hey — something happened. One important consequence of this thinking is: You should be OK if nobody picks up your event! This is a good litmus test if your event is really an event. If you do care that somebody is doing something with it, it would probably be better as a command.

- Commands are messages where you want something to happen. So you send a command to something that you know can act on it. And you expect it to do it. There is no choice. It might be still asynchronous though, so it is not guaranteed that you get an immediate reply.

I talked about that at length in my talk Opportunities and Pitfalls of Event-Driven Utopia (2nd half).

If you need a good metaphor: if you send a Tweet, this is an event. You just tell the world something that you think is interesting. You have no idea what will happen with it, might be that nobody looks at it, but it can also trigger tons of reactions. You simply can’t know in advance.

If you want your colleague to do something for you, send them an email. This is a command, as you expect them to do something with it.

Of course you could also switch to synchronous communication and call them – still a command – just blocking and synchronous now. This is another important remark: commands or events are not about communication protocols. Of course it is intuitive to send events via messaging (topics) and do commands via REST calls. But you could also publish events as REST feeds, and you can send commands via messages.

This means that the process has to be run synchronously until it gets an error. After that it should roll back to the last commit point and give the caller the error message.

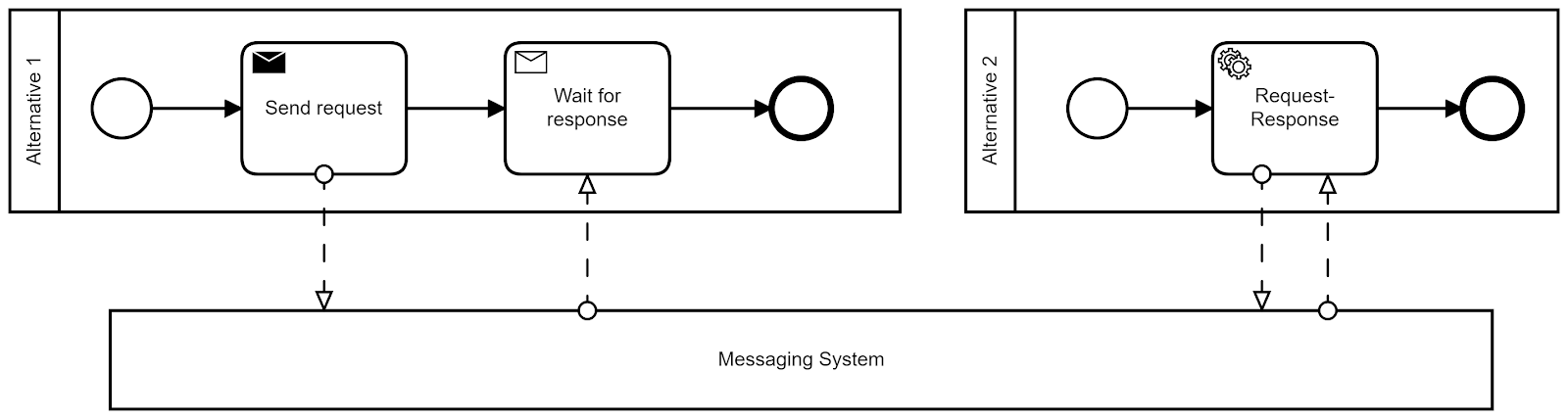

This is a super interesting topic. We build architectures more and more based on asynchronous communication. In some situations you still want to return synchronous responses, e.g. when your web UI waits for a REST call.

At least most projects still think they need that. I doubt that we need it that often, but we should think twice about user experience and frontend technologies. I wrote about it in Leverage the full potential of reactive architectures and design reactive business processes.

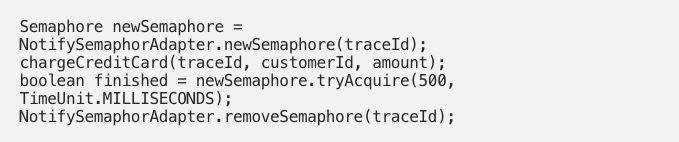

But let’s assume that we need that synchronous response. In this case you have to implement a synchronous facade. In short, this facade waits for a response within a given timeout. For Camunda BPM I did an example with a semaphore once (not the only possibility of course — just an example):

For Camunda Cloud (Zeebe) we even have this functionality built in with awaitable workflow outcomes.

Q: How to handle distributed transactions in an event-driven microservice choreography?

A couple of years back I wrote Saga: How to implement complex business transactions without two-phase commit — which might be a bit outdated, but still gives you the important basics. Or if you prefer you might tune into this talk: Lost in transaction.

TL-DR: You can’t use technical ACID transactions with remote communications, so never between microservices. You need to handle potential inconsistencies on the business level with one of three strategies:

- Ignorance: Sounds silly, but some consistency problems can be ignored. It is important to make a conscious decision about it.

- Apologies: You might not be able to avoid wrong decisions because of inconsistencies, but take measures to recognize and fix that later. This might mean that you need to apologize for the mistake — which might still be better, easier or cheaper than forcing consistency.

- Saga: You do the rollbacks on the business level, for example in your workflows.

Q: Can you give us an example of the saga pattern being used with BPMN?

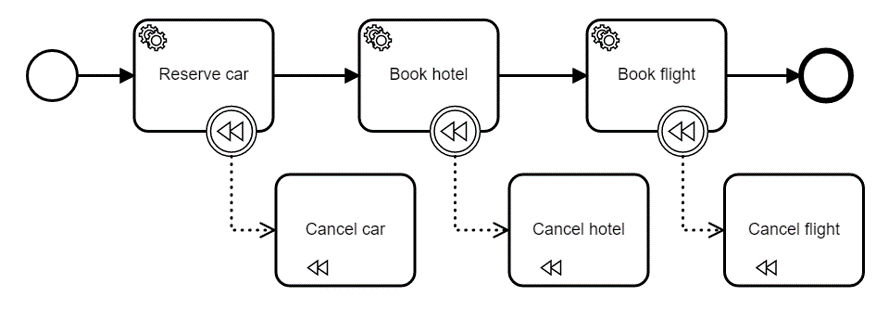

This continues the answer from the last question. So a Saga is a “long-lived transaction”. One way to implement this is by using BPMN compensation events. The canonical example is this trip booking (I also used in Saga: How to implement complex business transactions without two-phase commit):

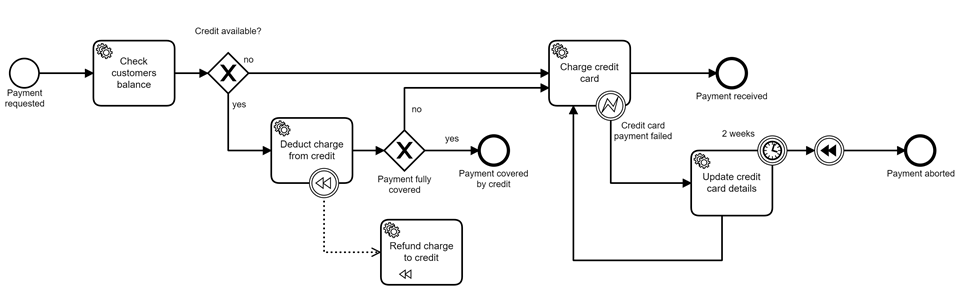

Using the order fulfillment example from the webinar, you could also leverage this for payments. Assume you deduct money from the customer’s account first (e.g. vouchers) before charging the credit card. Then you have to roll that back in case the credit card fails:

Q: How to use compensation with microservices?

You could see two examples in the last answer, I hope that helps. There is also sample code available for these examples on my GitHub. More info can also be found in the Camunda docs.

Q: How to correctly use retries?

Please have a look in the documentation – two places are worth checking: Transactions in Processes (as the foundation) and Failed Jobs for the specific retry configuration.

Q: Does Camunda support restartable and idempotent process?

Yes! For idempotent start, typical strategies are (quoted from Remote workers and idempotency):

- Set the so called businessKey in workflow instances and add a unique constraint on the businessKey field in the Camunda database. This is possible and you don’t lose support when doing it. When starting the same instance twice, the second instance will not be created due to key violation in this case.

- Add some check to a freshly instantiated workflow instance, if there is already another instance running for the same data. Depending on the exact environment this might be very easy — or quite complex to avoid any race condition. An example can be found in the forum.

In Zeebe we built-in some capabilities for idempotent start using unique “message keys”, see A message can be published idempotent.

You can easily restart workflows as you can learn about in the docs. Note that this might conflict with unique business constraints added for idempotency.

Q: I worry that applying automation (analytics) to existing workflows (i.e changing it, instead of automating some parts of an existing workflow) might not correlate to manpower requirements. For example, if all the databases were integrated (linked) based on some arbitrarily decided key — then critical information of (say) a patient connected with an issue referenced in another data set might require a “nurse” to verify the correctness of a record which was not previously required because the innate reasoning of an experienced staffer delivered these “interpretations” successfully — How could “experience” be grafted into the process?

This is quite a lengthy question and hard to answer without further refinement. But, as I was a consultant for a long time, I’ll answer it anyway 🙂 I might be way off — then just send me an email and I am happy to refine my answer.

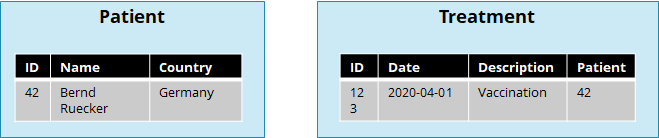

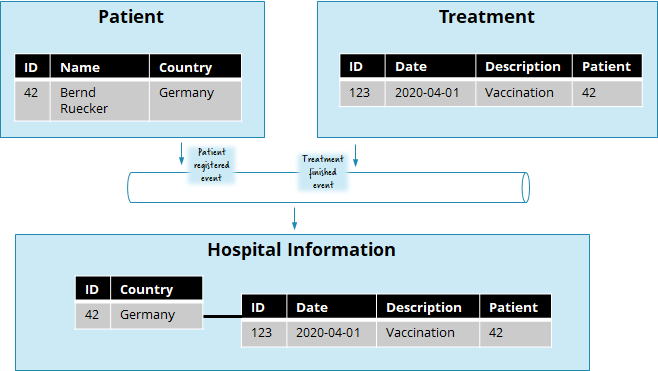

If you separate business logic into independent microservices, you can indeed no longer use database consistency checks (like foreign keys) or query capabilities spanning data from multiple microservices. Let’s use the example given in the question:

I could insert a treatment, where the patient id is invalid. And I could not easily answer the question, which people in Germany received a vaccination in April.

Both are true. But, this is the intention of the design! You want to probably evolve the treatment microservice independently of the patients. Maybe you will do treatments online in the future, where patients are registered differently? Maybe you have different patient microservices depending on location? It’s hard to discuss without a real use case at hand.

So you have to tackle these requirements on a different level now. First you could think of a specific microservice that is there purely for data analysis and now does data from both microservices. Like a data warehouse or the like. You might use events to keep that in sync.

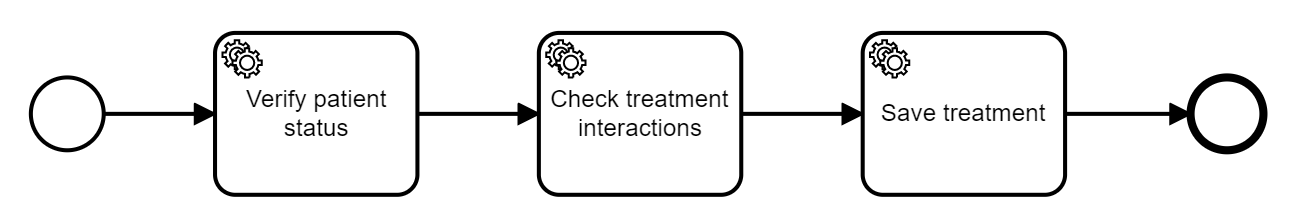

And second you will probably have workflows that care about consistency. So, for example, you could think of a workflow to register a new treatment:

This could live within the treatment service. Then it might ask the patient service if the patient is registered and valid. Another design could be that the treatment microservice also listens to all events and builds a local cache of patients, so it can validate it locally. And a third design is that there might even be a separate microservice that is responsible for planning treatments, that leverages the other two. Planning a treatment might get more complicated anyway — as you might need to check interactions with treatments in history and much more.

I could go on for ages, but the bottom line: it all depends on how you design the boundaries of your microservices.

If you get them right, you will not have too many of these problems. If you do them in an unfortunate way, you might get in trouble. Very often microservices boundaries don’t follow the static entities (= tables) as you might think in the first place.

Q: Do you have microservices to manage areas like complex ordering including package sales, bundling with many pricing options? Or services that could aid in converting product design into the bill of material used for the production line?

Once again these questions need some additional discussion to be clear what is asked. From what I read I would simply say, that it depends (of course ;-)).

You might add logic around package sales and other complex requirements into the order fulfillment microservice. You might also decide that this should be a separate microservice. The important thing is that it matches your organization structure. So if one team should do it all, why not have one microservice? If it is too much for a team, it does make sense to split it up.

In the latter case you need to think about the end-to-end business process, so especially about how you can include that special package sales service without hard coding it at many different places.

In the example from the webinar I could imagine that the button (=checkout microservice) or some complex package sales microservice emit the order submitted event, and order fulfillment takes it from there. But looking into more details it gets complicated quickly (what’s with payment? What if I can’t send one package? …?).

This is super interesting to discuss, but only makes sense in real-life scenarios. I am happy to join such a discussion — ping me!: https://berndruecker.io/bio.php

Ready for more?

Next week we’ll be diving into stack & technology questions. But if you can’t wait until the next blog, you can check out the original here on my Medium site.

Automate Any Process, Anywhere

Digital transformation initiatives can’t avoid all potential roadblocks. Learn how to overcome them when they arise.