Editor’s Note: This post originally appeared on Bernd Rücker’s blog and was cross-posted here with Bernd’s permission. Thanks Bernd!

Your company might want to go for a microservice architecture and apply workflow automation (I do not go into the motivation why in this blog post, but you might want to read about 5 Workflow Automation Use Cases You Might Not Have Considered or BizDevOps — the true value proposition of workflow engines.) This sets you in company with a lot of our customers. Typically, you will have questions around:

- Scope and boundaries (“what workflow do you want to automate and how is this mapped to multiple microservices or bounded contexts in your landscape”). To limit the scope of this post I spare this topic today, but you might want to read into Avoiding the “BPM monolith” when using bounded contexts or Real-Life BPMN.

- Stack and tooling (“what kind of workflow engine can I use?”)

- Architecture (“do I run a workflow engine centralized or decentralized?”)

- Governance (“who does own the workflow model and how does it get deployed?”)

- Operations (“how do I keep in control?”)

In this blog post I give some guidance on the core architecture decisions you have to make. I will give simplified answers to help you get started and gain some first orientation on this complex topic.

As all theory is gray I want to discuss certain aspects using a concrete business example which is easy to understand and to follow along. Using this I go over the following aspects in order:

- Track or manage — choreography or orchestration?

- 3 communication alternatives: Asynchronous communication using commands and events, RPC-ish point-to-point communication, work distribution using the workflow engine

- Central or decentralized workflow engine

- Ownership of workflow models

Business example

The example I use in this article is a simple order fulfillment application available as the flowing-retail sample application with source code on GitHub. The cool thing about flowing-retail is that it implements different architecture alternatives and provides samples in different programming languages. All examples use a workflow engine, either Camunda BPM or Zeebe. But you can transfer the learnings to other tools — I simply know the tools from my own company best and have a lot of code examples readily available.

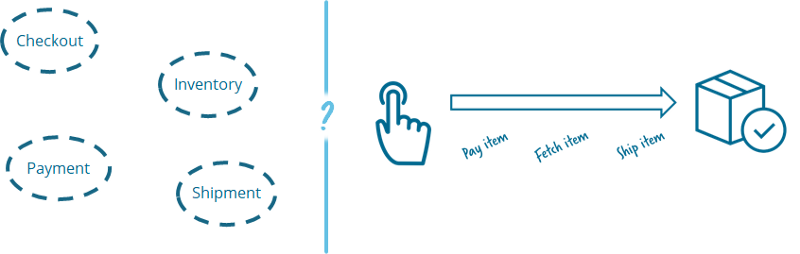

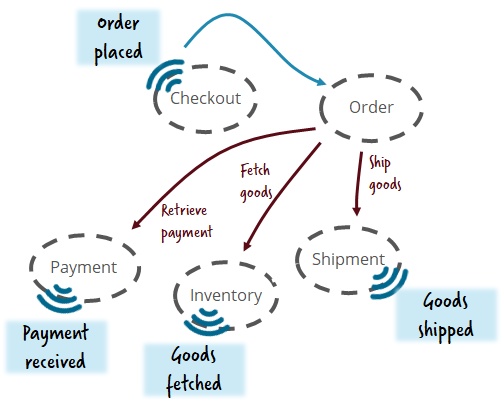

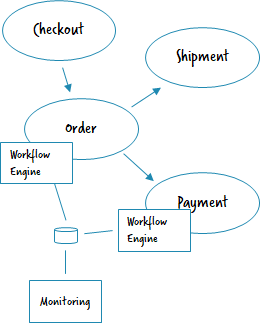

Let’s assume you want to implement some business capability (e.g. order fulfillment when pressing an Amazon like dash button) by decoupled services:

Track or manage? Choreography or Orchestration?

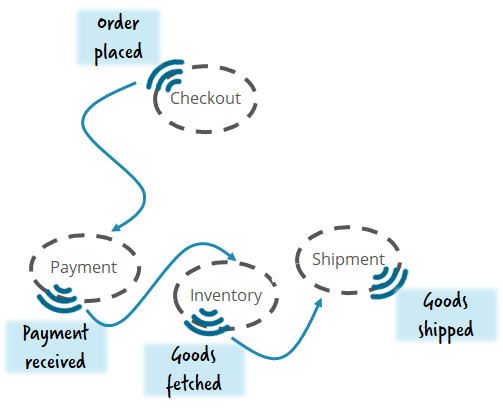

One of the first questions is typically around orchestration or choreography, where the latter is most often treated as the better option (based on Martin Fowler’s Microservices article). This is typically combined with an Event-driven architecture.

In such a choreographed architecture you emit so-called domain events, and everybody interested can act upon these events. It is a broadcast. The idea is that you can simply add new microservices which listen to events without changing anything else. The workflow as such is nowhere explicit but evolves as a chain of events being sent around. The danger is that you lose sight of the larger scale flow, in our example the order fulfillment. It gets incredibly hard to understand the flow, to change it or also to operate it. And even answering questions like “Are there any orders overdue?” or “Is there anything stuck that needs intervention?” is a challenge. I discuss this in my talk Complex event flows in distributed systems (recorded e.g. at QCon New York or DevConf Krakow).

You can find a working example of a pure choreography here: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java/choreography-alternative

Tracking

An easy fix can be to at least track the flow of events. Depending on the concrete technical architecture (see below), you could probably just add a workflow engine reading all events and check if they can be correlated to a tracking flow. I discussed this in my talk Monitoring and Orchestration of Your Microservices Landscape with Kafka and Zeebe (recording from Kafka Summit San Francisco).

![]()

Flowing-retail shows an implementation example using Kafka and Kafka-Connect: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java/choreography-alternative/zeebe-track and https://github.com/berndruecker/kafka-connect-zeebe.

A journey towards managing

This is non-invasive as you don’t have to change anything in your architecture. But it enables you to start doing things, e.g. in case an order is delayed:

![]()

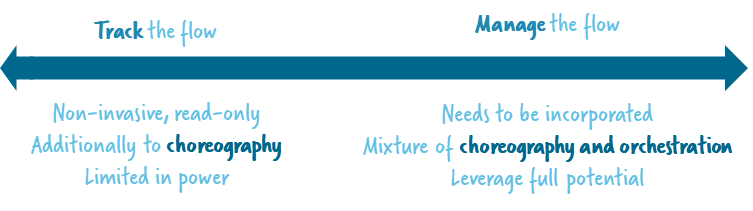

Typically, this leads to a journey from simply tracking the flow towards really managing it:

Mix choreography and orchestration

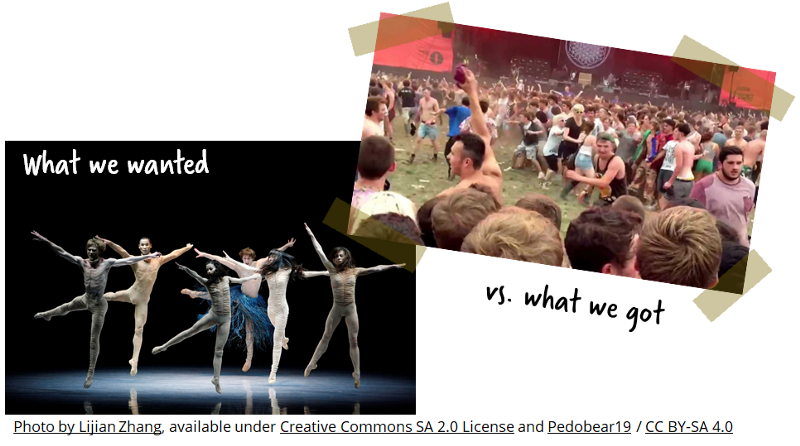

A good architecture is usually a mixture of choreography and orchestration. To be fair, it is not easy to balance these two forces without some experience. But we saw a lot of evidence that this is the right way to go, so it is definitely worth investing the time. Otherwise your choreography, which on the whiteboard was a graceful dance of independent professionals, typically ends up in more like a chaotic pogo:

In the flowing-retail example, that also means you should have a separate microservice for the most important business capability: the customer order!

The role of the workflow engine — three architecture alternatives

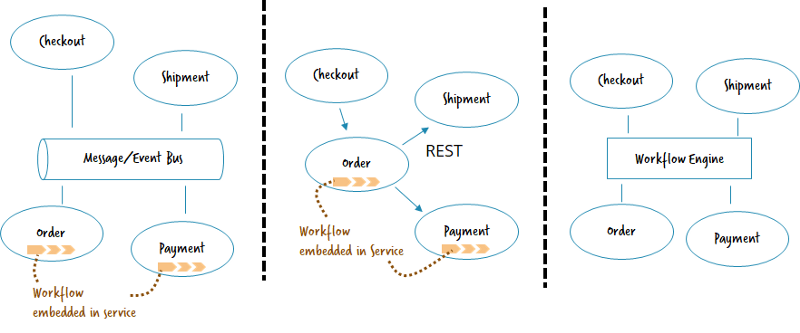

But how can you set up an architecture using a workflow engine to achieve this balance? Let’s simplify matters and assume we have a greenfield and only three architecture alternatives we can choose from (so no hybrid architectures or legacy).

- Asynchronous communication by commands and events (normally using a message or event bus)

- Point-to-point communication by request/response (often REST)

- Work distribution by workflow engine

We’re not yet looking at whether to run the workflow engine centralized or decentralized, which is a separate question tackled afterwards.

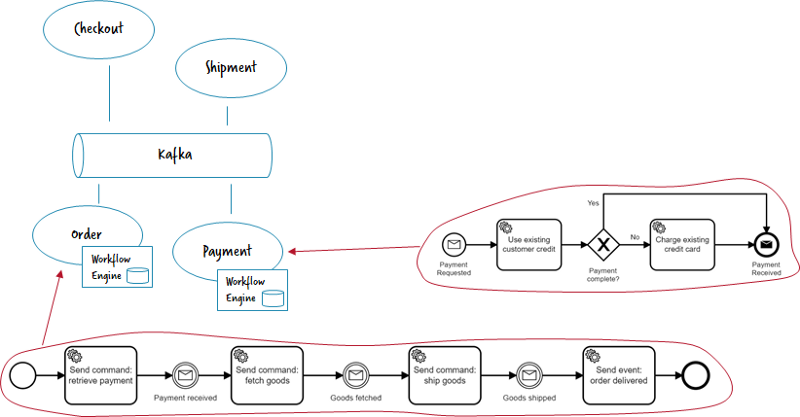

Asynchronous communication by commands and events

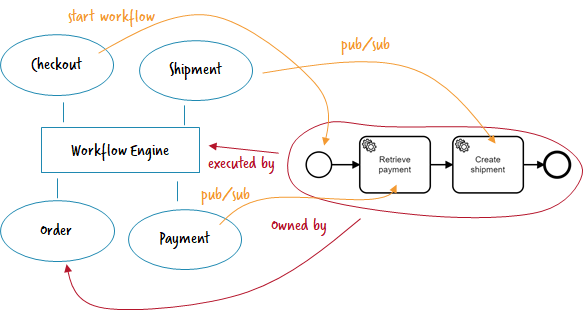

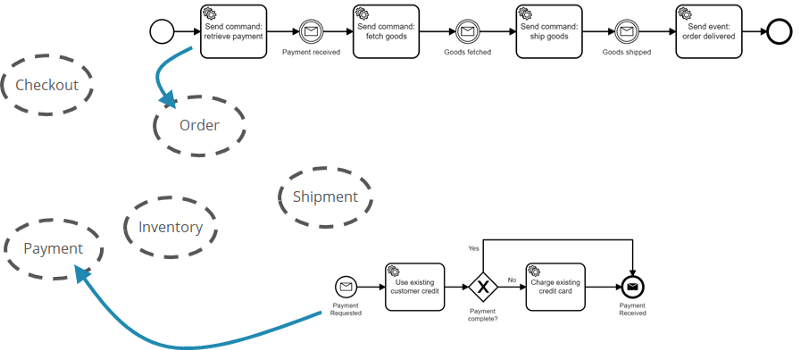

This architecture relies on a central bus for asynchronous communication. Different microservices connect to this bus. Orchestration logic and respective orchestration flows are owned by the microservices. Workflows can send new commands to the bus (“hey payment, please retrieve some money for me”) or wait for events to happen (“whoever is interested, I retrieved payment for O42”).

- Typical tools: Kafka, RabbitMQ (AMQP), JMS.

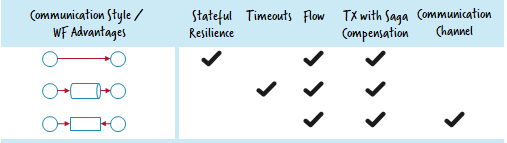

- What the workflow engine does: timeout handling, managing activity chains / the flow, support stateful enterprise integration patterns like aggregator or resequencer, consistency and compensation handling aka Saga patternas discussed in my talk “Lost in transaction” (recorded e.g. at JavaZone Oslo).

- Implementation example: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java

- Pro: Temporal decoupling of microservices; event-driven architecture applied right can reduce coupling; many failure scenarios (like e.g. response messages that are missing) are transparent to the developer, so he properly thinks about these situations.

- Con: Requires message or event bus as central component, which is not easy to operate. Lack of operations tooling for these components leads to effort going into homegrown “message hospitals.” Most developers are not so familiar with asynchronous communication.

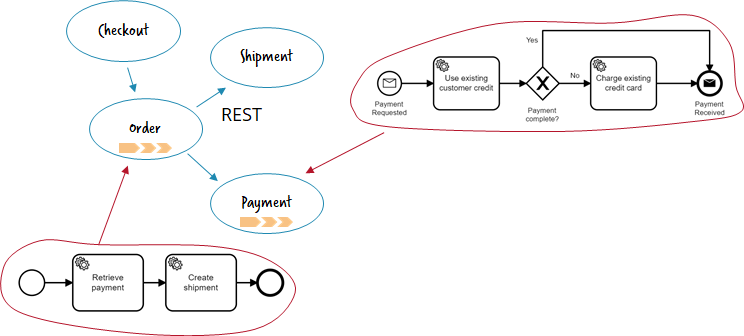

Point-to-point communication by request/response

In this architecture you simply actively call other microservices, most often in a synchronous, blocking way. The most prominent way of doing this is REST. Endpoints are typically retrieved from a registry. The workflow engine can orchestrate the REST calls and also help with challenges of remote communication — a topic I discussed in detail in my 3 pitfalls of microservice integration article (also available as talk, recorded e.g. at QCon London).

- Typical tools: REST, SOAP, gRPC; Could also be implemented with blocking messaging using request/reply queues e.g. in RabbitMQ.

- What the workflow engine does: stateful resilience patterns (like stateful retry), timeout handling, managing activity chains / the flow, consistency and compensation handling aka Saga pattern as discussed in my talk “Lost in transaction” (recorded e.g. at JavaZone Oslo).

- Implementation example: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/rest

- Pro: Easy to setup and understood by most developers; good tooling available.

- Con: Calls look like they were local, so developers often forget about the complexity of distributed systems; requires resilience patterns to be applied (e.g. Circuit Breaker, Stateful Retry, …).

Work distribution by workflow engine

In this architecture the workflow distributes work among microservices, which means it becomes some kind of bus itself. Microservices can subscribe to certain work of a workflow and get tasks via some kind of queue.

- Typical tools: External Tasks (Camunda BPM) or Workers (Zeebe).

- What the workflow engine does: communication channel, timeout handling, managing activity chains / the flow, consistency and compensation handling aka Saga pattern as discussed in my talk “Lost in transaction” (recorded e.g. at JavaZone Oslo).

- Implementation example: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/zeebe

- Pro: Easy to setup; good operations tooling.

- Con: Workflow engine becomes a central piece of the architecture and needs to be operated appropriately; communication between microservices only via workflows — or a second way of communication needs to established (e.g. REST or Messaging).

Thoughts and recommendation

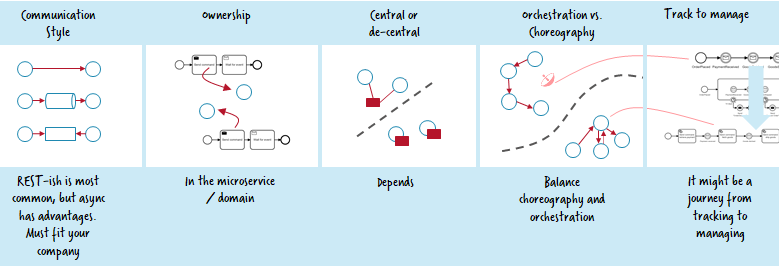

As always it is hard to give a clear recommendation. Normally I try to figure out what currently is already established in the company and base my decision on gut feeling about what can be successful in that environment.

For example, if a customer doesn’t have any experience with Kafka or Messaging, it will be very hard to establish this on the go. So they might be better of using a REST-based architecture, especially if, for example, they are deep into Spring Boot, making some of the challenges relatively easy to solve. However, if they strategically want to move towards more asynchronism, I personally support that , but I still want to make sure they are really able to handle it. If a customer already embraces Domain-driven design (DDD) and events, or even leverages frameworks like Akka or Axon, an event-driven approach that includes the workflow engine may be the best option.

So, there is a wide range of possibilities, and I think all options can be totally valid. Ask yourself what fits into your organization, what tools you already have and what goals you are after. Don’t forget about your developers who have to do all the nitty-gritty hard work and need to really understand what they are doing. And don’t forget about operations to make sure you really have fun when going live.

Central or decentralized workflow engine?

If you want to use the workflow engine for work distribution, it has to be centralized. In the other alternatives you have two and a half options:

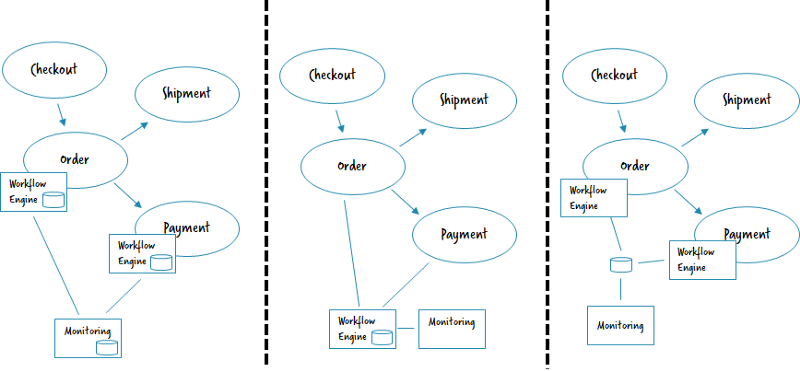

- Decentralized engines, meaning you run one engine per microservice

- One central engine which serves multiple microservices

- A central engine, that is used like decentralized ones.

A good background read on this might be Architecture options to run a workflow engine.

Decentralized engines

With microservices, the default is to give teams a lot of autonomy and isolate them from each other as much as possible. In this sense, it is also the default to have decentralized engines, one workflow engine per microservice that needs one. Every team can probably even decide which actual engine (product) they want to use.

- Implementation example: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java/order-zeebe/

- Pro: Autonomy; isolation.

- Con: Every team has to operate its own engine (including e.g. patching); no central monitoring out-of-the-box (yet).

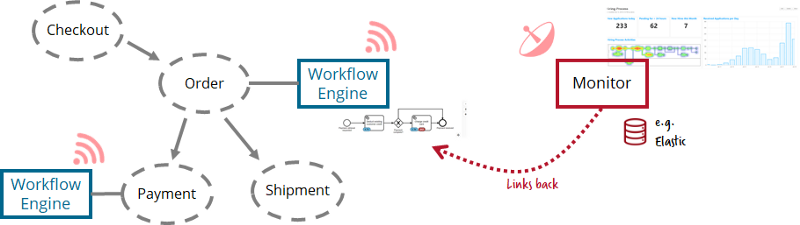

Typically monitoring is discussed most in this architecture: “How can we keep an overview of what is going on”?

It is most often an advantage to have decentralized operating tools. As teams in microservice architectures often do DevOps for the services they run, they are responsible to fix errors in workflows. So it is pretty cool that they have a focused view where they only see things they are responsible for.

Central monitoring with decentralized engines

But often you still want to have a general overview, at least of end-to-end flows crossing microservice boundaries. Currently customers are often building their own centralized monitoring, most often based on e.g. Elastic. You can now send the most important events from the decentralized engines (e.g. workflow instance started, milestone reached, workflow instance failed or ended) to it. The central monitoring just shows the overview on a higher level and links back to the decentralized operating tools for details. In other words, the decentralized workflow engine handles all retry and failure handling logic, and the central monitoring just gives visibility into the overall flow.

In our own stack we start to allow certain tools to collect data from decentralized engines, e.g. Camunda Optimize or Zeebe Operate.

- Implementation example: A simplified example is contained in https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java/monitor

One central engine

To simplify operations, you can also run a central engine. This is a remote resource that microservices can connect to in order to deploy and execute workflows. Technically that might be via REST (Camunda BPM) or gRPC (Zeebe).

- Implementation example: https://github.com/berndruecker/flowing-retail/tree/master/kafka/java/order-zeebe

- Pro: Ease of operations; central monitoring available out-of-the-box

- Con: Less strict isolation between the microservices, in terms of runtime data but also in terms of product versions; central component is more critical in terms of availability requirements.

If you want to use the workflow engine as work distribution you need to run it centralized of course.

Central engine, that is used like decentralized ones

This approach typically needs some explanation. What you can do in Camunda is to run the workflow engine as library (e.g. using the Spring Boot Starter) in a decentralized manner in different microservices. But then you connect all of these engines to a central database where they meet. This allows you to have central monitoring for free.

- Pro: Central monitoring available out-of-the-box.

- Con: Less isolation between the microservices, in terms of runtime data but also in terms of product versions, but actually moderated by features like Rolling Upgrade and Deployment Aware Process Engine.

Thoughts and recommendation

I personally tend to favor the decentralized approach in general. It is simply in sync with the microservice values.

But I am fine with running a central engine for the right reasons. This is especially true for smaller companies where operations overhead matters more than clear communication boundaries. It is also less of a problem to coordinate a maintenance window for the workflow engine in these situations. So as a rule of thumb: the bigger the company is, the more you should tend towards decentralization. On top of organizational reasons, the load on an engine could also make the decision clear —as multiple engines also mean to distribute load.

Having the hybrid with a shared database is a neat trick possible with Camunda, but should probably not be overused. I would also limit it to scenarios where you can still oversee all use cases of the workflow engine and easily talk to each team using it.

Of course, you can also mix and match. For example, you could share one database between a limited number of microservices, that are somehow related, but other teams use a completely separated engine.

However, a much more important question than where the engine itself runs is about ownership and governance of the process models:

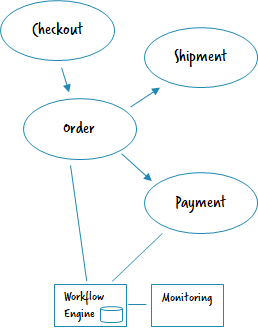

Ownership of process models

Independent of the physical deployment of a workflow model (read: where the engine runs) it must be crystal clear who is responsible for a certain model, where it is maintained and how changes are deployed.

In microservice architectures the ownership of a workflow model must be in the team owning the respective domain.

In the flowing-retail example there are two workflow models:

- Order fulfillment: This belongs to the order fulfillment business capability and has its home in the order microservice.

- Payment: This is owned by the payment microservice.

It is really essential that you distribute the ownership of parts of the business process fitting to your domain boundaries. Don’t do a BPM monolith — where e.g. the order fulfillment process handles business logic and other details related to payment — just because you do a workflow model.

The “orchestration process”?

I am often asked: But where is “the orchestration process?” That is easy: In my understanding of microservices, there is no such thing as an orchestration process.

Often people mean end-to-end business processes, like order fulfillment in the above example. Of course, the end-to-end process is highly visible and important, but it is domain logic like everything else and goes into a microservice boundary, in our example the order microservice. In that sense the order microservice containing end-to-end orchestration logic might be very important — but organized the same like other microservices as e.g. payment.

When saying “orchestration process,” some people mean domain logic that only involves the flow — so the respective microservice might not have other logic (no own data, no own programming code, …). That is fine — but it should still be a microservice as even this logic needs clear responsibilities. And often the logic grows over time anyway.

Summary

The described topic is complex and there are no easy-to-adopt-in-all-scenario-answers. I hope this post gave you some orientation. Let’s quickly recap:

You need to chose your communication style: Asynchronous, RPC-ish or work distribution using the workflow engine. Depending on that choice the workflow engine can do different favors for you:

The ownership of workflow models must be in the domain of the respective microservice. The workflow should clearly concentrate on that domain.

You can run the workflow engine centralized or decentralized.

Track or manage —you should strive for a balanced mix of choreography and orchestration.

Thanks to Tiese Barell and Mike Winters for helping to improve this post.

Bernd Ruecker is co-founder and developer advocate at Camunda. He is passionate about developer friendly workflow automation technology.

Follow Bernd on Twitter. As always, he loves getting your feedback. Send him an email to get in touch.

Start the discussion at forum.camunda.io