Please note: This blog post is the Part One of a two part series. If you are looking for Part Two then you can find it here.

If your organization relies on BPM and your process definitions are considered to have “long running” process instances (perhaps due to user tasks etc.), then there comes a time when your organization needs to define the process instance migration strategy. This blog will show you how to define your migration strategy as a business process and to use BPMN to help control different scenarios during your custom migration.

A common challenge in the BPM world when planning your SDLC comes when a new iteration of your process model arrives…

If you have process instances that run and complete in a very short period of time, then having a new version of the process definition arriving on the scene might not be a big deal. All requests for new process instances are simply created from the new definition and old process instances can quickly expire on their own.

But in the real world, that is not always the case. You might work in an organization where your process definitions are designed to have instances that complete in a matter of hours, or days, or even months/years. Some common use cases include process definitions that:

- Have many human user tasks

Have intermediate timer events that allow the process instance to simply wait for a certain amount of time - Have message event tasks that are waiting to receive a message from some other slow moving process instance.

In long running process instances, a new process definition that substantially alters the workflow in some way might pose a great challenge. How we handle this scenario at the strategic level depends on a few different points:

- Is this an urgent release? Does this new version fix an existing urgent/blocker bug of some kind?

- Is there a time constraint here? For instance, does this new version enforce some kind of new regulatory standard that must be in place by a certain date/time by law?

By answering these questions at the strategic level, we have a better idea how to answer the more operational question.

Can we let the old process instances age and complete on their own while new process instances are spawned off of the new definition? Or it is imperative that we migrate existing process instances to work off of the new definition?

If you find yourself in the migration scenario and you are using Camunda BPM, then you are in luck! Camunda has a rich Migration API. Not only is this available directly in the Camunda Java API, but it also has handy REST API endpoints wrapping this code as well.

With the community edition of Camunda BPM, you can use the Camunda documentation to guide you in creating the payload object that defines the migration mappings for that call. The enterprise version of our Business Activity Monitoring tool (Camunda Cockpit) provides a nice user interface wizard for:

- Allowing the user to graphically map the migration of a process instance token from Task A in version X to Task B in version Y.

- Defining the filtered list of process instances that are participating in the migration.

- Generating the migration payload for you.

- Initiating the migration.

While this Migration API is very powerful, it might not handle every scenario. For instance, what if you had a large number of instances to migrate? You might not want to overload the job executor with handling a request to migrate all of these at one single moment. Instead you might want to do them in smaller batches. Also, what if your migration requires that you alter the process instance variable data and values in order for the migration to work properly?

What we are discussing here sounds a lot like a business process, doesn’t it? Why not use BPMN to model our migration process?

In this use case, we have a process that loses a User Task from Version 1 to Version 2.

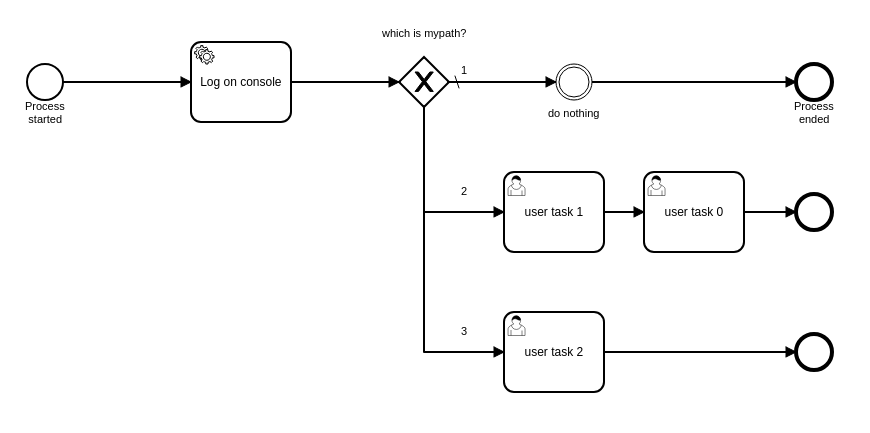

Version 1 looks like this. Notice on path 2 that there is a “User Task 0”.

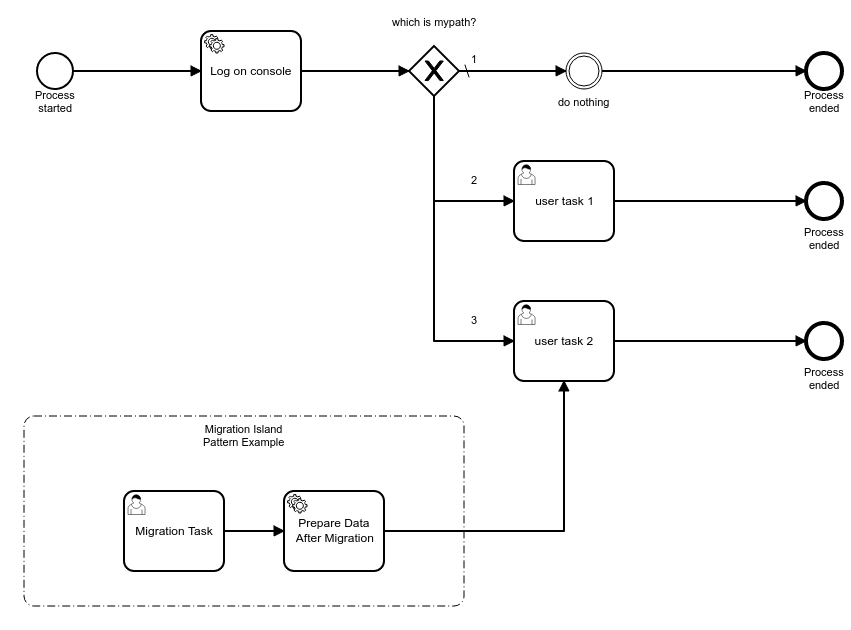

In Version 2, “user task 0” no longer exists, so we need to migrate all existing tokens on “user task 0” to “user task 2” over on path 3. The problem is that the development team is telling us that if we do this token migration directly, then those process instances might not function properly. Some kind of “data massage” is required in order to make sure that migration from “user task 0” to “user task 2” happens without incident.

(NOTE: For the purposes of this exercise, the actual data that needs to be prepped for this to work correctly is irrelevant and out of scope. Let us just pretend that many things need to be carefully changed for the migration to work correctly.)

So the development team decides to use a “Migration Island” pattern for this migration. They will use the process migration functionality of Camunda to migrate tokens of “user task 0” from Version 1 to the “Migration Task” user task shown in Version 2. The only purpose of this “island” is to accept tokens during a process migration process. The process model design should allow no other means to arrive at this island in the flow.

The DevOps team also has a concern during this migration. They are concerned that there might be more than 50,000 instances to migrate on deployment night, and that the migration itself might cause unexpected load on the infrastructure. Therefore, they are asking the development team to migrate in controlled batches, setting a proper maximum number of process instances to migrate during each batch. For instance, let us say 500 at a time.

In Part 2 of this blog post, we will demonstrate the solution to this use case.

If you can’t wait until Part 2, join me at CamundaCon Live on April 23rd, where I’ll demo this solution live in my presentation: Process Migration 201: Tips, Tricks, and Techniques.

Plus if you would like to run some of these example projects yourself, please feel free to pull them from Git here.

See you at CamundaCon!